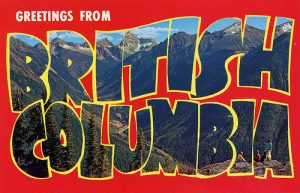

From its initial conception to its forthcoming catalogue/book, Peter White’s curatorial project “It Pays to Play: British Columbia in Postcards, 1950s-1980s” has generated great interest as it brings together a selection of over two thousand postcard views of B.C. in both a visually stimulating, conceptually inquisitive, and nostalgically rich exhibit. Presented on the gallery walls and in vitrines under a strictly gridded layout, the internal logic and dynamics of these mass-reproduced objects are underlined and point toward an archeological priority. This indexical frame provides a rare opportunity to critically survey an extensive field of visual representation that has helped to define British Columbia’s landscape in relation to constructions of nature, progress and industry.

Organized along approximately thirty categorical headings as broad as “Leisure,” “Architecture,” “Landscapes,” “Industry” and “Urban Views,” and as specific as “Roads in the Landscape,” “Cars in the Landscape,” “People in the Landscape,” “Winter” and “Trail B.C.,” these postcards at first appear to be part of an obsessively objective attempt to create an encyclopaedic archive. However, looking closer we find that this inventory also provides a conceptually interesting examination of the advent of relatively inexpensive, but technologically sophisticated forms of colour reproductions. In these “chromes,” deeply entrenched formal conventions and new aesthetic devices come into play with an emerging world of industrial development, commerce and new urban communities, revealing both banal and idealized images of leisure and tourism.

Reintroduced in the present as collected evidence for an investigation into a nearby past, these postcards appear on one level as either sadly naive, comically kitsch or highly nostalgic. On another level they also give insight into a stage in the formation of a touristic gaze that helped to define prosperity and progress in Canada’s most western province. As markers of an expansive tourist industry, these postcards are part of a larger scopic regime that helps to ensure that the field of vision governing land and leisure supports this economy alongside notions of industrial growth. While this ideological structure is formally referred to in the exhibition’s layout and the seemingly objective picturing of B.C., it is when the individual categories and the postcards are analyzed more closely that the reification of cultural commodities and sites break down most visibly to reveal both a production and displacement of social desires.

To point the gallerygoer in this direction, White has provided a number of helpful leads starting with the form and image of the invitation card for the exhibition which is appropriated from one of many unusual pictures included among the otherwise standardized and typical postcards. As if mimicking the formal composition of Manet’s L’Exposition Universelle 1867, this 1950s image presents an unabashed modern vision of nature subjugated to commerce, industry and recreation. Elevated high above the city of Trail at a picnic area, two casually well dressed couples are seen contemplating this “progressive” fusion of industry and nature as smelters pierce the landscape in front of them. Surveying the exhibition, we find dozens of other similar scenes where a landscape, otherwise defined as “empty,” is rendered productive by the incursion of industry and technology. Among the most dramatic of these must be Cominco’s Warfield Fertilizer Operation at Trail or Bennett Dam whose architectural vocabulary and utopian pictorial space resembles the technological dreamscapes of Moon-Base Alpha.

Interestingly enough, there is the odd postcard that (incidentally or not) reveals the tensions accompanying this economical expansion. For example, in Bridge to West Quesnel in British Columbia’s Famous Cariboo Country, a railway bridge traverses the Fraser River linking Quesnel’s growing community in the distance to our immediate foreground where a young native man dressed as a rancher poses contemplatively in front of a small and scraggly tree. With an analogously strange sense of narrative, a postcard in the “Rogers Pass” section of the exhibit features a pre-adolescent girl dressed in red standing alone overlooking a brand new highway that cuts through a mountain range otherwise untouched by modernity.

Back-projected onto one of the gallery walls, the postcards are magnified to provide yet another space for critical inquiry. While enlarged to the size of traditional history paintings, they are simultaneously referencing family vacation slide presentations and information/advertising strategies found at park offices across the province. Repetitiously changing the images at five second intervals, enough time has been allotted for us to get a closer glimpse at the cards while also directing our attention to their mechanically reproduced nature.

As a strategy, repetition is utilized in other ways as well. In a particular section, a set of identical postcards are displayed under their own separate heading. In another, we find botanical postcards repeated and organized in patterns that abstractly resemble landscape garden design. Dislodged from the exhibition’s otherwise consistently systematized layout, this section’s overt “playfulness” stands out as an odd curatorial decision slightly out of touch with the presentation’s general conception. More subtly, and arguably more interestingly, the postcards are often repeated in different categories. For example, a card showing a pink motel appears under the headings “Motels,” “Pink” and “Architecture,” drawing attention to an inevitable failure within indexical structures such as this archive to “contain” information.

While these self-reflexive curatorial interventions do offer very important critical insight into the visual history of British Columbia, one can not help to speculate how the exhibition could have been structured differently to provide a more historically specific analysis. Wondering what subjective reminders might exist on the flip-side of these cards (the flip-side is never revealed), this particular visitor would also have been interested in a closer historical reading of individual sites as well as the specific contexts which informed the production of individual cards. Recognizing the parameters and limitations of White’s project, one hopes that the forthcoming publication will push the socio-political tensions closer to the surface by providing a more direct discussion of the displacement caused by the economic and technological optimism represented in these byproducts of capitalism’s ever-expanding tourist industry.