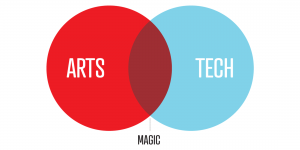

The arts are very much concerned with today’s technologies. Numerous works reflect this in one way or another, even if the techniques and machines are far from apparent in most cases, and have a role only in the processes of creation. Few are indifferent to these new technologies and the issues they raise, for they force us to reconsider certain questions about art, society, the economy, the environment, communication, and our view of the world. In this respect, Eric Raymond refers to a “conditioning” of our preoccupation with machines.

WHAT TECHNOLOGIES ARE EXAMINED IN THIS ISSUE?

Video should perhaps be mentioned first, as it is the oldest of the recent technologies. This constantly evolving medium is the physical support (magnetic tape) associated with the very first conquests of the image: photography and cinema.

The subsequent technologies cannot be regarded as supports in the 19th-century sense of the world. The arrival of the computer as an artistic tool represents a break with certain modes of apprehending the world and of reproducing its image. Henceforth, its representation would be calculated and rendered interactively. Practices derived from computer technology include digital images and sound, virtual reality and on-line artwork.

The hybrid forms and intermediate phases that combine computer and video, digital images and real images, for example, are also important steps that should not be overlooked.

The medium of video is now thirty years old. This span of time may seem short compared to cinema and photography, which have passed their centenary, but long compared to the spate of new technologies that have emerged in recent days.

This seniority, as it were, has allowed video to incorporate a critical dimension that puts into perspective certain concepts that have arisen from the modern aesthetic tradition.

The methods and means used primarily in fields of communication, such as the Internet, give rise to an entirely new set of aesthetic issues; as yet, we do not have enough data to judge whether or not these will generate new artistic practices. Nancy Shaw considers this question in social and economic terms, questioning the notion of interactivity and the museological institution.

Certain sites, however, have already been explored by artists who are testing the modes and applications.

As for virtual reality, experiments are being conducted primarily in the scientific and military sectors. For artists, virtual reality would seem beyond their reach. Only those researchers affiliated with scientific experimentation centres have access to these tools and the necessary technical support. The hypermedia (CD ROM, DVD), on the other hand, were appropriated by some artists as soon as they came out. The medium of virtual reality can be viewed in terms of a certain continuity, as it was prefigured by the cassette and video installation.

The viewer is now more than ever at the centre of things. Certain technologies require that the viewer be intimately connected with the work (hypermedia, for example), while others operate according to a hybrid mode which forces the viewer to navigate between extremes. Does the interactivity mentioned in each of the articles stem from the practices themselves or is it an extension of the “place of the viewer”?

So far, technological theory has predominated over technological practices. A considerable number of articles, reviews and books have advanced the most extravagant theses, but always based on research into the specificity of the various practices, isolating them from any type of contextualization. This phenomenon has generated utopian claims – sometimes paranoid, sometimes euphoric – about tools which require manipulation and transformation, and about practices which still await analysis and conceptualization.

The theoretical texts on the subject are at the inevitable stage of defending specificities and isolating the territory from any cultural context. Parachute’s second issue on this theme looks at the problem from this perspective.

David Tomas speaks of the schizophrenia resulting from this dual attitude: a critique of the quest for progress and a search for contexualization on the one hand, and a questioning of newness and a search for specific identity on the other. As the interviews indicate, most artists pay scant attention to these new techniques, and in fact show a certain opportunism: they use them for a predetermined project with a fixed idea in mind. Rarely, these artists admit, do they engage in technological research or contribute to technical advances. It is the theoretical project, the ideas and concepts, that are of lasting significance, not the methods employed.

Visual artists like to work alone, whether in the studio or elsewhere. They are therefore generally on the lookout for technologies which are easily accessed, the less complicated the better. For this reason, the machines they use have most often reached a stage of wide commercialization, being easy to master and accessible to all.

A number of exhibitions have attempted to mark out the common ground between the visual arts and the new technologies. Without doubt, the exhibition which has had the most impact in this respect is “Les Immateriaux,” conceived by Jean-Francois Lyotard and held at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1985. More oriented towards the relationship between reproducible works and the visual arts, “Passages de l’Image” (conceived by Raymond Bellour, Catherine David and myself) presented eighteen photographic, cinematographic, videographic and computer-based works at the Centre Georges Pompidou in 1990. “L’Ere binaire,” conceived by science professor Charles Hirsch and held at the Musee d’lxelles in Brussels in 1992, exhibited a number of art works created by computer or generated by machines. “Press Enter (Between Seduction and Disbelief),” organized by Louise Dompierre, Derrick de Kerckhove and Robert Riley for the Power Plant in Toronto in 1995, unveiled a number of potential concepts stemming from technological works. “Artifices,” an event held in Saint-Denis (France), presents every two years a selection of technological works of an artistic nature. In Montreal, “Images du Futur” has organized international exhibitions of art and new technologies on a yearly basis since 1985. The Guggenheim Museum SoHo, in New York, recently opened a program dedicated to multimedia art with the presentation of “Mediascape.”

Certain specialized centres producing and exhibiting works and engaging in theoretical reflection have also arisen over the last decade: ZKM in Karlsruhe, ICC in Tokyo, and the production centre in Banff.

The development of technologies may appear to be linked with the development of memory. Today, numerous artists explore the archives and reassemble the fragments of history. New technologies would seem to help us preserve the memory of time and history.

Instead, the reverse has occurred. The more the various media have improved and advanced, the less they have withstood the ravages of time. Papyrus is still our most reliable support. Paper, paradoxically, which was invented years later, is less stable than the papyrus of our ancestors. The same is true of technological supports: CD ROM is already considered less durable than magnetic tape. Computers have an announced life span of three years; video material, five. Ironically, these technologies which were supposed to preserve our historical memory have instead accelerated the process of amnesia.

This historical loss would seem to coincide with a territorial expansion. Network technologies, which everyone speaks of today and which many of us are starting to experiment with, denote a profound change in our sense of perceived space, which is no longer seen from the single, homogenous point of view of the Renaissance tradition. Our world-view has become anisotropic and entangled in a complex, inter-relational web.

WILL ARTISTS EMBRACE THESE NEW MEDIA?

The ideas that may result from this new vision of the world, from our permanent relationship with others, from our new presence/absence with regard to the individual body, from our conscious relationship with the environment, from the unstable economies of countries and continents – will these ideas require new artistic practices?